For you to keep progressing you must, over time, continue to challenge your body by stressing it more than it’s used to so that it is challenged and therefore must adapt to overcome the stress put upon it.

Put simply, progressive overload, in terms of an exercise or movement pattern, is making that exercise or movement pattern harder.

Now most people’s “go-to” for achieving progressive overload is to lift more weight than in previous weeks or training phases and blocks, and rightly so. Adding more weight is probably the simplest way to achieve progressive overload with any exercise.

I mean, if you can Deadlift 100kg for 5 reps, then the next week you increase the weight to 102.5kg for 5 reps you’ve made the exercise harder, challenging the body more than the previous week and therefore achieved progressive overload.

So, adding weight is the easiest and most obvious choice, but it’s not the only approach you can use, nor should it be.

What if you need to create a different stimulus than just that of adding more weight?

What if you train at home and have limited options when it comes to adding weight, how do you create progressive overload?

What if your confidence isn’t quite there yet to lift heavier weights, but you still want to progress your training?

You need to have other approaches in your toolbox.

You can’t just have a hammer.

So, here are 5 other “tools” that you can use to progress your training that don’t involve you going heavier.

No.1: Increase your reps, volume or training density:

This option is usually people’s next “go-to” after the option of increasing weight. To progress an exercise, and make the same weight more challenging, you can simply change the rep scheme or increase your overall training density or volume.

Let’s say you just finished a 4-week training phase and ended up lifting 100kg for 3 sets of 5 reps in a deadlift. Here’s how you could progress this next phase, without necessarily adding more weight to the bar.

Option A: Aim to lift the same weight for more reps

Last phase: 3×5 @100kg

This phase: 3×6-8 @100kg

Option B: Aim to lift the same weight for more training volume

Now, this will also be achieved by taking the Option A approach, or you can take a slightly different approach if going for more reps doesn’t appeal to you.

Last Phase: 3×5 @100kg [1,500kg of training volume]

This Phase:

- Week 1: 4×5 @100kg [2,000kg of training volume]

- Week 2: 5×5 @100kg [2,500kg of training volume]

- Week 3: 6×5 @100kg [3,000kg of training volume]

*training volume is calculated as sets x reps x load

Option C: Aim to increase your training density.

Training density is essentially how much work you complete in a set time. So, to challenge the body using this approach you primarily have 2 options.

1: Aim to achieve the same volume of work in less time…

- last phase: 3×5 @100kg achieved in 10 total minutes

- this phase: 3×5 @100kg with the aim of completing it in less than 10 minutes

2: Aim to achieve more volume of work in the same amount of time…

- last phase: 3×5 @100kg achieved in 10 total minutes

- this phase: aim to complete more than 3×5 @100kg in 10 minutes [so 4, potentially 5 sets in the same time]

No.2: Change your rep tempo

There are multiple ways to change a rep’s tempo, each creating a slightly different training stimulus and resulting in a different amount of Time Under Tension [TUT] for the particular rep, set or exercise it’s used for.

Utilising techniques like slow eccentrics, pauses, stato-dynamic tempos and adding in additional ¼ reps and ½ reps can be very useful, not only for making an exercise harder, but also for strengthening up certain weak links you may have within a lift.

Let me give you an example of how each of these techniques could be used to make an exercise harder.

Slow eccentric tempo:

For this approach, you are going to purposefully slow down the lowering phase of the lift each rep. A common practice is to slow that phase of the lift down to somewhere between 3-10s every rep.

By taking this approach you will make the exercise harder by increasing the TUT of each rep and therefore the set as well, whilst also increasing your eccentric strength in that lift.

Example:

Last phase: 3×5 w/ no tempo focus

This phase 3×5 w/ 4s lowering every rep

Adding a pause to the lift:

Like the above approach, for this method, you are also going to purposefully slow down each rep’s overall tempo, this time by adding in a pause during a certain part of the lift. This pause will usually be for somewhere between 3-10s every rep.

Like slowing down your eccentric speed, by taking this approach you will make the exercise harder by increasing the time under tension of each rep and therefore the set as well, and depending on where you choose to pause, you can strengthen up specific weak points within that lift as well.

Example:

Last phase: 3×5 Front Squat w/ no tempo focus

This phase 3×5 Front Squat w/ 3s pause at the bottom of every rep

Stato-dynamic tempo:

This technique involves slowing down both the eccentric [lowering phase] and the concentric [lifting phase] of an exercise, whilst ensuring you don’t pause or lockout at the top or bottom of the lift as well. The aim is to keep constant tension on the working muscles.

Example:

Last phase: 3×10 Goblet Squat w/ no tempo focus

This phase: 3×10 Goblet Squat w/ a Stato-Dynamic Tempo of 3-0-3-0 [3s lowering, 3s lifting and 0s pausing or locking out]

Additional ¼ reps and ½ reps:

This is probably the least common of the approaches used to increase time under tension, but don’t let that fool you, they’re incredibly effective.

With this approach you are going to add in an additional ¼ or ½ rep to your usual rep to increase the reps overall time under tension, usually performed between the eccentric [lowering phase] and the “full” concentric [lifting phase].

These additional ¼ or ½ reps can also be positioned within in the rep to help bring up a weak point as well as the additional ¼ or ½ increases the overall time under tension spent in that weak point area.

Example:

Last phase: 3×10 Goblet Squat 2/ no tempo focus

This phase: 3×10 Goblet Squat w/ an additional ¼ rep added at the bottom of each rep.

*which would look like this: squat down, come ¼ of the way up, go back down, then stand all the way up. That equals 1 rep

No.3: Increase the movement Range of Motion [ROM] of an exercise

Now, this approach isn’t always possible for some exercises, but for those that it can be used with it creates a great challenge and opportunity for further progression in a movement or exercise.

The increased Range of Motion stimulus can, and usually does, help drive up your ability and progress in the “original” movement as well.

Let me give you a couple of examples to show you what I mean.

Example 1:

Last phase: 3×5 deadlifts

This phase 3×5 4” deficit deadlifts

This approach requires you to stand on a 4” platform whilst still keeping your deadlift start position on the ground. This is going to increase your overall deadlift range of motion by 4”, it will make the start of each rep much harder and very often helps to make a person stronger off the floor when they return to a “normal” deadlift.

Example 2:

Last phase: 3×10 split squats w/ dumbbell goblet hold

This phase: 3×10 front foot elevated split squats w/ dumbbell goblet hold

This approach requires you to place your front foot on a 6-9” step or box whilst performing your split squat. This method is going to increase your range of motion and, when done with the correct technique, will create a greater training stress on the quadriceps of the lead leg than a standard split squat will.

No.4: Change the load position on your body for the exercise

I’m a big fan of this progression approach, especially for lower-body single-leg work. Too often people feel the need to change a movement for something new at the end of a training phase, when in most cases a simple loading method change is all you need to keep progressing an exercise and make it harder.

As an example of just how many options are available to you when it comes to loading an exercise, here are a few examples of how you can load a Split Squat.

Split squat w/ dumbbell goblet hold

Split squat w/ 2x dumbbells held down by your sides

Split squat w/ 1x dumbbell contralateral Suitcase hold

Split squat w/ 1x dumbbell ipsilateral suitcase hold

Split squat w/ 2x kettlebell front Rack hold

Split squat w/ 1x kettlebell contralateral front rack hold

Split squat w/ 1x kettlebell ipsilateral front rack hold

Split squat w/ barbell zercher hold

Split squat w/ barbell front rack hold

Split Squat w/ Barbell on Back

That’s 10 variations right there just for one exercise, and there are more you could do for a split squat as well. If you did each one for a 4-week training phase, that’s 40 weeks of split squat variations right there for you.

No.5: Change the equipment you’re using to load the exercise

This is another method that often gets forgotten as a means to make an exercise harder.

Just take another quick glance above at my split squat example you’ll see the movement examples include dumbbells, kettlebells and barbells, but you could also load the movement using bands, chains, a cable machine, a weight vest or a sandbag as well.

Each equipment type can, and will, create a slightly different challenge when used for the movement. This will create a different stimulus on the body and keep you progressing forward, often without the need to actually go heavier to achieve a greater challenge.

So now we’ve added those 5 tools to your toolbox when it comes to making an exercise harder do you want to see where the magic truly happens?

Of course, you do…

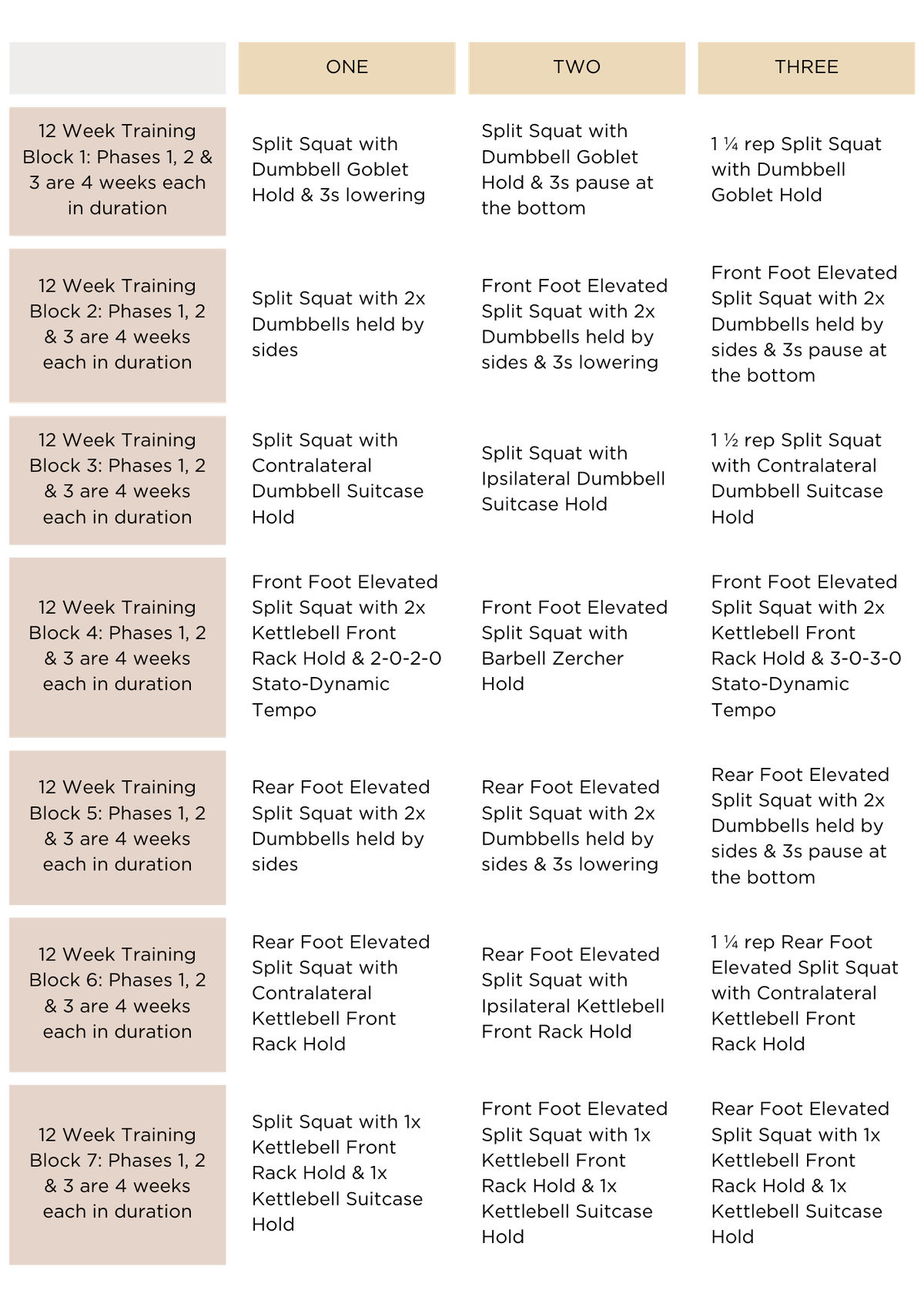

Behold, 84 potential weeks of training progressions for just 1 exercise using the 5 methods detailed in this article.

That’s over a year and a half of training options at your disposal to keep you moving forward.

If you want to take advantage of years of potential training progression options that will help you make any exercise harder without always having to add weight to an exercise, add these 5 tools to your toolbox…

…and watch your training continue to go from strength to strength.